How much sacred space do we find in our lives these days?

For many, not much.

Especially if going to church or hanging out in libraries is not your thing.

Does that mean we can’t or don’t keep sacred space?

I think we can. And do.

What is Sacred Anymore?

Everything!

Sacred comes from the Latin word for holy.

Nowadays, we define sacred as connected with God (or the gods) or dedicated to a religious purpose and so deserving great respect.

For some, that comes with a lot of baggage.

Sanctuary also comes from the Latin word for holy and means a sacred place. A place one is safe. A place of respect. A place to be.

Just as a sanctuary can be one’s home or favorite park, we can create sacred space and times and practices and rituals anywhere in our lives.

We set the intention, we eagerly express our love and pay close attention. Committed, respected, honored. Over and over and over again.

While these are integrated into our everyday, that does not make them secular.

In his TEDTalk and book about The Art of Stillness, Pico Iyer describes his evolving practice of a secular Sabbath.

Right now, this doesn’t make sense to me. Secular meaning “attitudes or activities that have no spiritual basis.”

For me, Sabbath and my other spiritual practices are absolutely about connecting with my spirit and the Spirit, the life force that runs through everything, and with my communities.

This divine connection is sacred and holy. And present every moment of my life.

Especially on Sabbath.

Sabbath Time

Iyer reminds us of how Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel called Sabbath “a cathedral in time rather than in space.” He further described it as the one day a week we take off becomes a vast empty space through which we can wander, without agenda, as through the light-filled passageways of Notre Dame. It’s like a retreat house that ensures we’ll have something bring and purposeful to carry back into the other six days.

“This is what the principle of the Sabbath enshrines,” Iyer said.

Sounds pretty sacred to me!

So how do we keep this time sacred?

We keep this time sacred by defining and refining what brings us closer to the Source.

“Often what seems necessary in the moment can often wait, making way for a day that is holy, set apart and different,” wrote Shelly Miller in Rhythms of Rest.

The day becomes celebratory and special, revered and desired.

And, so we set boundaries that help us and others to be in this sacred time – together or apart, as needed.

“Sabbath restrictions on work and activity actually create a space of great freedom; without these self-imposed restrictions, we may never be truly free,” said Wayne Muller in Sabbath.

Miller agrees that it’s not about specific rules, but rather boundaries that allow greater flexibility. She offers the reminder that with practice, over time, we achieve a Sabbath heart and resolve remains steadfast whatever the context.

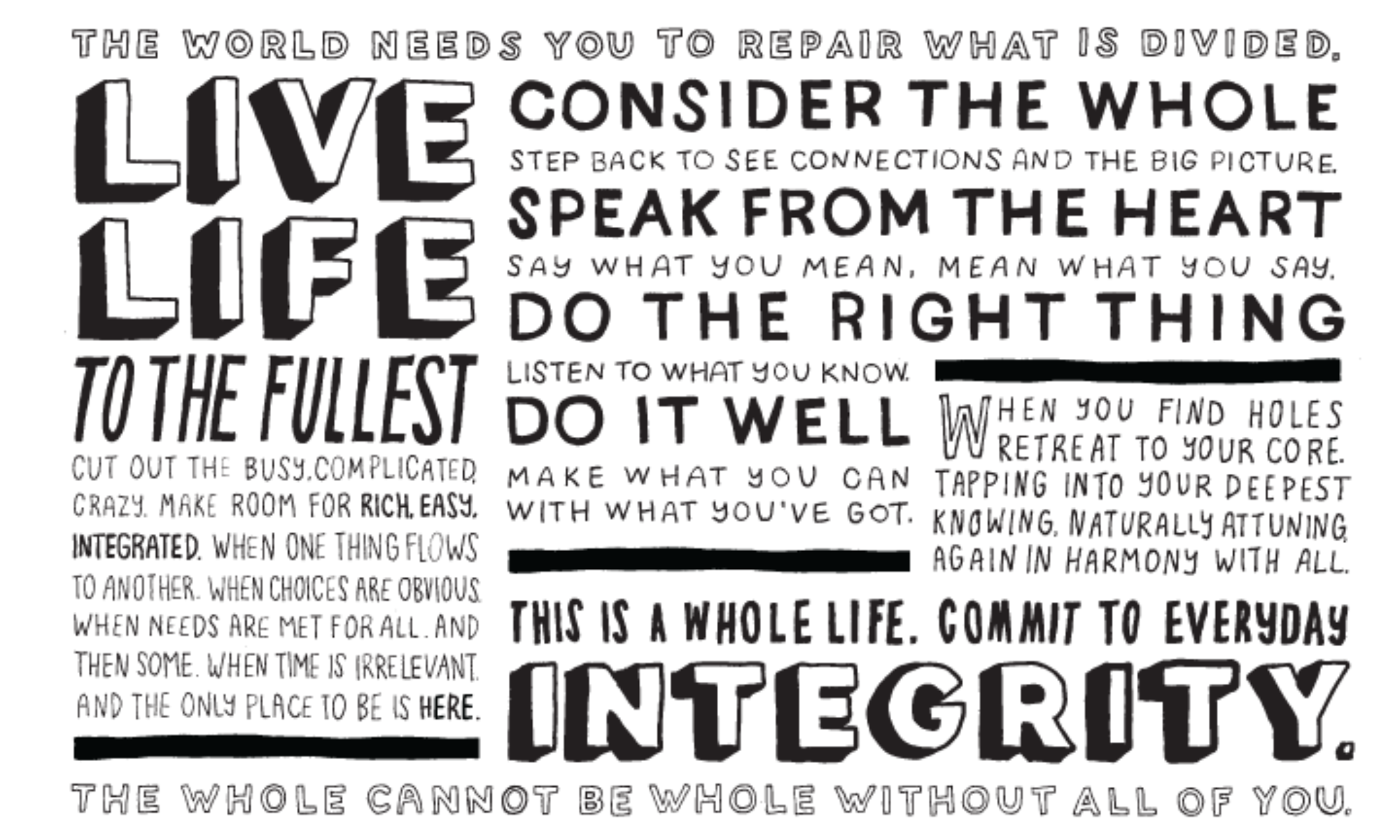

When we can speak clearly and from the heart about why Sabbath time is sacred, is special and different, then others will understand, respect and support us in keeping sacred space.

And, if they don’t, that says a lot too!

What to Keep Out

The universal tradition in this break, this pause, this sacred time of being gone sabbathing looks different for everybody nowadays.

The main ways this time becomes holy, set apart, different is:

- Not working, including paid work and informal work, domestic work, caregiving, volunteering

- Being offline and disengaged from technologies like the internet, email, and often social media

- Disengaging from measured time, schedules and planning

Easier said than done. Absolutely.

Especially if your spirit leads you along a spiritual path that is outside of one formal organization or community, like me.

While I have many spiritual communities, none observe Sabbath in the way that I do.

I have made this sacred time my own. As many others are doing as well.

In his book The Promise of a Pencil about his rapid and successful entrepreneurial journey to create schools in third world countries, Adam Braun talks about his own practice.

He doesn’t call it Sabbath, but given his Jewish roots, I have a feeling it is similarly inspired.

He described, instituting a personal policy of going off email from Friday night until Sunday morning. He used the weekends to rest, rejuvenate and reconnect with those he cherished most.

This was tough to do in the passion-driven and all consuming startup and nonprofit worlds Braun exists in. It required clear boundaries around work and online activity.

His email response to a colleague is a great template for explaining these boundaries to others:

“I just want to be open with you. I recently put a practice into place where I go off email from sundown Friday to Sunday morning, to make sure I stop working and spend quality time with my loved ones. I also find it makes me more energized for the next week ahead if I’m not on email over the weekend, and it help to avoid burnout.”

Now, what coworker wouldn’t understand that?

And, if they don’t, that says a lot too!

The key is to be forthright with others about when our sacred time is, what it looks like, and why it’s important, so that they can respect and honor it.

What to Keep In

Who knows, maybe they’ll want to join in?

For many, the invitation to rest and reset has never been offered or modeled.

Or there is a bad aftertaste from past experiences with organizations, rules and sacrifice. It is a sacrifice!

Sacrifice also comes from the Latin for holy. It is an act of giving up something valued for the sake of something else regarded as more important or worthy.

As Wayne Muller said in Sabbath, “It is too easy to talk of prohibition, but the point is the space and time created to say yes to sacred spirituality, sensuality, sexuality, prayer, rest, song, delight.”

The universal tradition in this break, this pause, this sacred time of being gone sabbathing looks different for everybody nowadays.

The main ways this time becomes holy, set apart, different is:

- Being, celebrating, worshiping, rejoicing, feasting, playing, loving

- Giving our undivided, loving attention to those in our lives and within touch, whether partner or child or cat or garden or self

- Living in the moment, going with the flow, unbound by schedules and planning

Rituals, or a series of actions, help set this time apart just as intentionally as boundaries.

Just as Miller said, as continued, dedicated practice becomes rhythm becomes tradition, these rituals become less learned and more intuited.

For many, Sabbath includes ceremonies to enter and exit this sacred time.

As well as special candles, prayers, spices and/or foods. And special activities like bathing or making love.

Inspired by Muller’s book, Sabbath, which includes lots of ideas for rituals, using a Sabbath box is something that’s new to my practice in the last year.

This box holds matches, a candle and a poem to enter Sabbath. Index cards with my fundamental precepts of what matters most, poems, a pen and special pocket notebook for capturing divine musings during the day. A bag of spices, a tiny bowl and prayers to exit Sabbath. Often, I turn off my phone and put it away in the box for the day, as I would with a watch if I wore one.

And, my box can even travel with me when I’m away on Sabbath!

Sabbath Worthy

“When I ask myself if the activity is easy and if it makes me feel lighter, my answer determines how I choose to spend time on Sabbath,” wrote Miller.

I completely agree.

I find this applies to finding restorative “activities” and especially to who I spend time with on Sabbath.

Is this person easy? Do they make me feel lighter?

Here Anne Morrow Lindbergh is reflecting on life in general within her book, Gift from the Sea, though is especially true on Sabbath:

“I shall ask into my shell only those friends with whom I can be completely honest. I find I am shedding hypocrisy in relationships. What a rest that will be! The most exhausting thing in life I have discovered is being insincere. That is why so much of social life is exhausting, one is wearing a mask. I have shed my mask.”

This begs the question: if someone is not “Sabbath worthy,” then how (and why) are we fitting them into the rest of our life, or our “shell” as Lindbergh says?

My tolerance and interest for activities and people, feelings and habits that do not align with this rhythm of balance has changed dramatically.

Sabbath has shown me what to keep out and what to keep in during my sacred time set apart each week.

And, over the years, these lessons have seeped into the rest of my days, into the whole of my life.

Join others from around the country in the next Sabbath Course as we explore and practice together, inspired by an interfaith, personal approach to this universal tradition. This 7-week course includes fun weekly activities, weekly community gatherings online and your own practice. You’ll experience what students describe as a “positive and significant impact on my personal growth and spiritual exploration.”